A group of architects and their supporters have a plan to transform unused buses into shelters and hygiene facilities for homeless people, and are now looking for funding and a nonprofit partner.

“This is not a solution to housing,” says Jun Yang, executive director of the Honolulu Mayor’s Office of Housing, “but, using what we have, why don’t we try something useful and helpful? These buses could create another layer of housing for those who can’t go into a shelter.”

Yang’s dream is to renovate about 70 of the city’s decommissioned buses, now sitting in the Middle Street bus barn, into sleeping buses with partitioned cubicles, and showering and lavatory buses. He says decommissioned Handi-Vans are smaller but can be refurbished for individual families who need more privacy and they can be locked for security. Yang says the city is “agreeable” to the repurposing the buses.

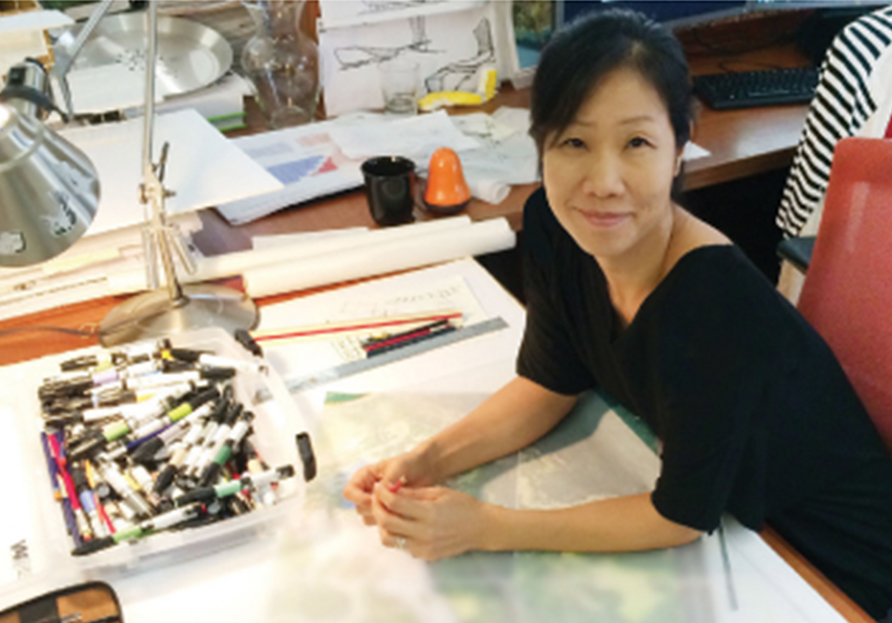

Ma Ry Kim, principal and design director at Group 70 International, is spearheading the pro bono effort. “We decided to call our project Lift, because when you ask someone for a ride, you say, ‘Could I have a lift?’ ” she says. “Also, it refers to our intent to uplift or elevate people by providing them with these facilities.”

The project is inspired by San Francisco’s launch of the privatized “Lava Mae” showering and lavatory buses for the homeless in 2014. (Lavame means “wash me” in Spanish.) Lava Mae’s architect/ designer, Brett Terpeluk, shared his experiences, ideas and designs with the local architects, who also found inspiration in mobile-gym “tumble buses” for children, bookmobiles, bloodmobiles and art buses.

“That’s what’s so fortunate about this ‘kit of parts’ design,” says Kim, describing the dual-purpose sleeping buses, in which the bunks can be stored underneath the floorboards. “Not only can the parts be easily assembled inside the bus, but they can also be easily stacked away during the day, so the bus can be used for other things, such as health exams or teaching or art therapy. And, because they’re buses, they can be driven to any place.”

Kim has worked a lot with orphanages and the homeless in Mozambique. “The human atrocity that you see in Africa and in other places is almost unspeakable, but the atrocity in Hawaii is pretty bad, as well,” she says. Kim says Yang often goes into the streets to do headcounts of the homeless and, one morning at 2 a.m., “He saw a 2-year old baby sitting on the street with nothing on but a diaper. And the baby was alone. Unfortunately, this is not uncommon.”

“Jun was very heartfelt about it, and said, ‘We have to do something.’ ” Kim answered the call. She brought along Reid Mizue, president of Omizu Architecture Inc., who previously did bus-design work and obtained the 1994 design specs for the city’s Gillig buses. Also part of the project are Ryan Sullivan, project architect at Group 70, who once submitted plans for a homeless housing project at UH; and Charles Siu, 23, architectural designer at Group 70, who’s handling the aesthetic design.

Yang says he knew that old Roberts Hawaii tour buses had been turned into shelters by the Evening Angels project previously run by homeless advocate Utu Langi, so he knew the concept could work in Hawaii. (Yang says Langi gave up the last of those buses in 2013.)

The personal hygiene buses are also an important part of the project, Mizue says. “We believe that even the most minimal of services we can provide to people can mean the most. A simple thing like a shower can mean a lot to someone who doesn’t have easy access to one,” he says.

Sullivan adds, “We want the feeling to be ‘high-end,’ so people won’t be ashamed of going inside. And the Lava Mae folks said the one thing people wanted most there was privacy, so they scheduled half-hour appointments for each person to use the hygiene bus, so they didn’t have to stand around outside.”

The muted-yellow buses are meant to be attractive, yet distinctive. Siu says the ohia flower design on the outside is to symbolize resiliency, as that’s the first flower to poke through the lava after an eruption.

Yang doesn’t yet have specific locations in mind for the buses, and the group is aware of the challenges presented by the need for a water source and wastewater disposal for the hygiene buses. But what the volunteer group says it needs now is for a nonprofit to take over the effort, and for those with money and resources to step forward to help execute their design.

“We’d like to get the buses out in the community as soon as possible, but just need the funding,” Kim says.

“The idea of using buses instead of shipping containers as shelters is much more humane. Buses are meant to carry people and they’re ergonomically designed for humans. I think people feel less boxed-in in buses and more free.”